Although most pigs in the UK are kept commercially and have veterinary care provided by veterinarians attending exclusively to pigs, there are a great many smaller holdings attended by mixed or general species farm animal vets who may lack confidence in pig management, handling and disease. In this article, the authors aim to equip general species vets with the basic tools required to: discuss relevant aspects of pig management, assess a sick pig and empower reasoned treatment choices.

Collecting a clinical history

Collecting a detailed clinical history is crucial to problem-solving sick pigs. Familiarity with basic aspects of pig husbandry will aid the veterinarian in asking meaningful questions, for which helpful resources are listed on the Pig Veterinary Society (PVS) webpage on resources/signposting for small-scale pig veterinarians (PVS, 2024). SRUC’s outdoor farrowing manual is also an invaluable resource (SRUC, 2019). Showing curiosity when visiting pig holdings will facilitate your understanding of normal management practices and how these vary between different owners and holdings.

For the sick pig, the standard formula for collecting a clinical history can be adapted with some species-specific language:

Ask open questions as much as possible during your history taking, just as you would for any other species. This is the best way to gather thorough information, avoid leading your clients’ answers and build your confidence in discussing pig problems.

Handling, restraint and physical examination

Many aspects of a pig’s physical examination are gathered ‘over the farm gate’, using a ‘hands-off-pig’ strategy. This is because of relatively fewer low-stress pig restraint methods – stress quickly obscures the values and behaviours the pig would otherwise exhibit. As shown in Figure 1, this includes assessing body condition and posture, skin abnormalities, behaviour and demeanour, character of faeces and more. Here, taking videos to show to colleagues and monitor clinical progression may be advantageous.

Clients can significantly impact whether their pigs can be handled by providing regular and sympathetic care. Vets can offer advice and assistance on how to proceed, but veterinarians must not put themselves or their clients at risk of harm. A helpful resource for owners is AHDB’s webpage and online module on moving and handling pigs (AHDB, 2025a).

Some form of restraint may be necessary for other elements of the physical examination. This includes taking a rectal temperature, for which the normal range is approximately 38.3°C to 39.5°C. Whilst it is good practice to auscultate the chest using a stethoscope, vocalisation frequently makes this unrewarding. Restraint may also be required to perform an obstetric examination or administer injections.

When considering a suitable restraint method, remember that pigs can be very strong and have a low centre of mass; if they feel threatened and can access an escape route, they will usually take it. Rather than using brute strength, pig handlers can, more effectively, use their knowledge of pig behaviour to their advantage.

For post-weaning pigs, assuming the pig can walk, the pig should be contained in a smaller and well-lit area, such as a pen, barn or small paddock with a strong perimeter. Feed can be used to encourage the pig into the corner of the pen or paddock. Then, the owner can come alongside with a large pig board (or any large, flat object, such as a sheet of plywood or a pallet with staggered slats). With the pig contained in this temporary chute, the veterinarian can stand or kneel behind them. Alternatively, and even more preferably, pig keepers can be encouraged to construct strong, semi-permanent handling facilities (Figure 2), into which pigs can be trained to voluntarily walk.

Even if the pig appears unable to move, suggesting it can be examined in recumbency, enter their personal space cautiously. Stress can quickly over-ride feelings of pain and lead to an aggressive and potentially dangerous animal.

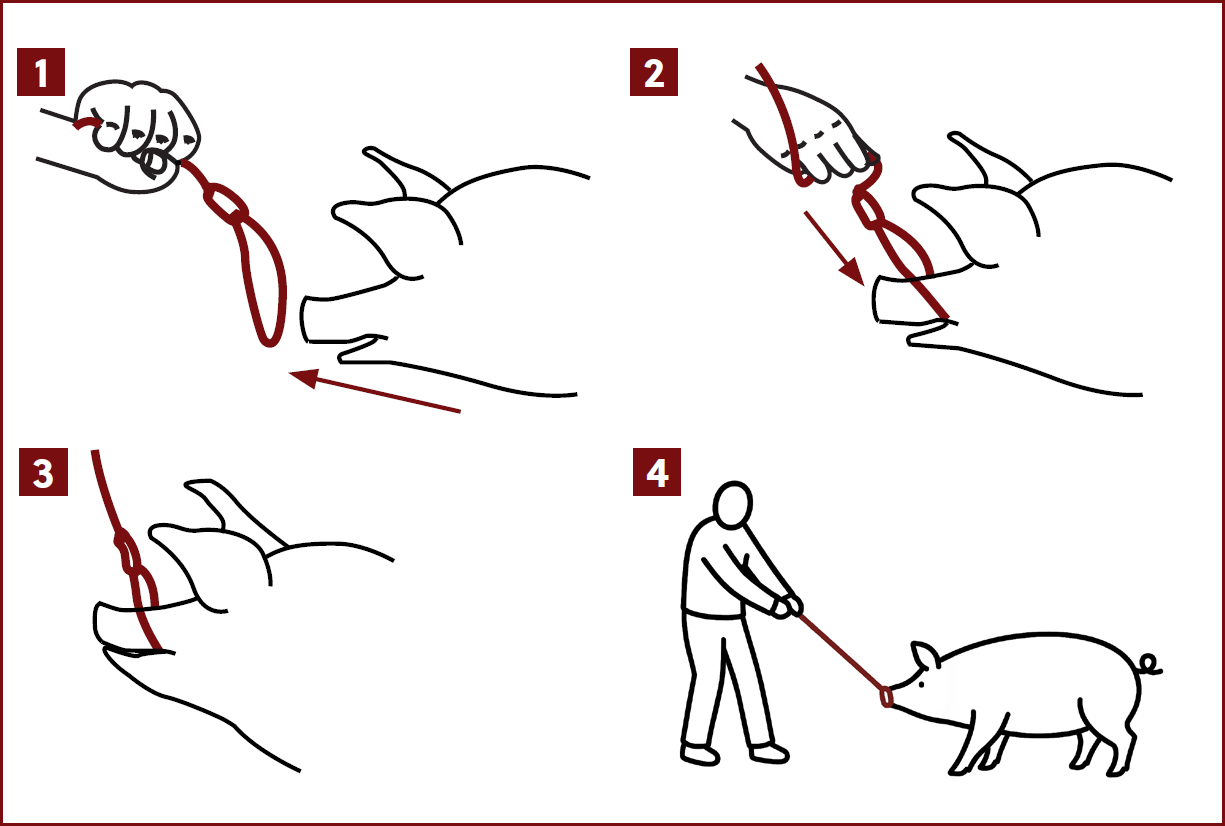

While a snare can be used to restrain a pig (and is essential for procedures like blood sampling), it requires a carefully instructed and relatively strong assistant to hold the snare while performing your examination/task. Owners should be warned that the pig may squeal loudly and continuously. It is also common for a sick pig not to show sufficient interest in the snare to allow correct placement. For these reasons, a snare is is not a suitable form of restraint for some situations, but can be applied using the steps shown in Figure 3.

Adopting a clinical-reasoning approach

While veterinarians may be tempted to reach for ‘antibiotics and pain relief ’ as a first-line approach to a sick pig, adopting a clinical-reasoning approach can enable more targeted and more appropriate interventions. This may improve the prognosis of the individual sick pig and the future herd, especially considering the risk of the development of antibiotic resistance as a result of inappropriate antibiotic use.

To adopt a clinical-reasoning approach, veterinarians should consider the case information collected in the context of possible differential diagnoses and disease pathologies. Helpful texts include Pig Diseases (Taylor, 2013), Diseases of Swine (Zimmerman et al, 2019) and Managing Pig Health (Muirhead et al, 2013).

At each stage of a clinical reasoning process, it is important to consider the suspicion of notifiable disease. This is achieved by cross-referencing findings with a good understanding of the characteristics of notifiable diseases in pigs. A resource, created by the Pirbright Institute and APHA, contains images of the clinical signs and pathology related to African swine fever (The Pirbright Institute and APHA, no date).

Suspicion of notifiable disease must be reported to Defra Rural Services Helpline on 03000 200 301 in England. In Wales, contact 0300 303 8268 and in Scotland, contact your local Field Services Office.

In the section below, the authors discuss three common scenarios. They describe how a clinical-reasoning approach could be applied to suggest suitable treatments, management strategies and future preventative measures. For more information on encouraging antibiotic stewardship when prescribing antibiotics to pigs, consult Scott et al, 2024.

Case 1

History

A two-year-old Berkshire boar has recently been hired onto a smallholding for breeding. The owner reports that the boar has been ‘off colour’, lethargic and only consumed half of his breakfast. On examination of the rest of the herd, some healing skin lesions were noted on a four-month-old gilt (Figure 4). The breeding pigs reared on the holding are vaccinated against erysipelas, having received an initial course at 6 months of age followed by boosters every six months.

Physical examination

The abnormal findings in this sick pig include being sternally recumbent and reluctant to rise, as well as having a rectal temperature of 40.5°C.

Discussion

Differential diagnoses for this boar include causes of lethargy and pyrexia in this age pig, the most common being a bacterial septicaemia. While a definitive diagnosis cannot currently be established, the clinical situation is consistent with erysipelas. Points to note include that the sick boar is of unknown vaccination status and has recently experienced stress associated with transport. While the vaccinated breeding herd appears unaffected, a young gilt (who has not yet received erysipelas vaccination) has healing skin lesions of a classic diamond, erysipeloid shape. A high rectal temperature commonly results from a bacterial septicaemia, as in this case.

It should be noted that erysipelas does not consistently cause the classic raised red, diamond-shaped lesions on the skin (Figure 5), and these can be challenging to see in animals with black skin (as in this case). Erysipelas can also result in lethargy and inappetence (as in this case), sudden death, lameness, red/purple blotchy skin and/or abortions. As vegetative endocarditis (Figure 6) is frequently found at post-mortem in pigs with erysipelas, the growth of affected but surviving animals may be limited.

Treatment and prevention plan

Treatment should include a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID). The animal should be isolated and provided with supportive care, including a warm, deep bed and access to appealing food and fresh water. Further guidance on managing hospitalised pigs is available from the PVS casualty pig document (PVS, 2013).

Given that erysipelas is the veterinarian’s most likely differential diagnosis from the information collected, use of an antibiotic to which the causative bacterium for erysipelas (Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae) is likely sensitive, constitutes a rational choice. This includes amoxicillin, which is considered a suitable first-line treatment for pigs when clinically required by PVS (2020), as described in their prescribing guidelines for antibiotics. Another key differential diagnosis for this sick pig – Streptococcus suis – is also likely to be sensitive to amoxicillin.

For future preventative actions aimed towards erysipelas, the herd’s vaccination programme could be brought forward to cover growing pigs (after their maternal antibodies have waned). In future, boars should be sourced from a vaccinated herd or, failing this, quarantined and vaccinated before mixing with sows for breeding. Other preventative measures may include periodic cleaning and disinfection of pig facilities, especially following observation of clinical signs of erysipelas; preventing contamination of pig food, feeders and drinkers with bird faeces; and practicing good rodent control. It is also important that veterinarians warn the owner that erysipelas can (rarely) cause disease in people, usually manifesting as skin infections. Appropriate personal protective equipment, including gloves, should be worn when handling pigs, especially when they are sick.

Although the treatment in this case may resemble an empirical response, by collecting a thorough history and applying knowledge of pig diseases, veterinarians can engage with their clients, provide sensible options for future prevention and be reassured that there is a logical framework underlining treatment choice.

Case 2

History

A first-lactation sow with 12 three-week-old piglets has become inappetent and lethargic. She is not currently receiving medication. The client presents a photograph of an unidentified substance found in the paddock (Figure 7).

Physical examination

Abnormal findings in the sick pig, include: a full bowl of this morning’s feed (consisting of large sow nuts); slightly puffy breathing accompanied by an increased respiratory rate; an arched back with teeth grinding; and a substance in the paddock that was believed to be vomit.

Discussion

A veterinarian can be confident that the mysterious finding on the ground is vomit because:

The arched posture, teeth grinding and general malaise are indicative of pain; as the pig’s gait appears normal, this pain is likely abdominal. Differentials for abdominal pain and vomiting vary but include gastric ulceration, foreign bodies, torsions/volvulus, peritonitis and/or a mixture of the above. Gastric ulceration is fairly common in sows at peak lactation, possibly due to the commonness of the risk factors for the condition in these animals, which include a reduction in feed intake, stress, and finely ground, pelleted feed. Figure 8 shows severe ulceration of the pars oesophagea of a pig, similar to what could be expected in this case.

Treatment and prevention plan

Although a definitive diagnosis cannot currently be reached in this case, several of the differentials listed tend to be catastrophic for the pig and are diagnosed post-mortem. As a gastric ulcer could be both a cause and a consequence of the clinical progression here, supportive therapy focused on gastric ulceration appears, to the authors, to be the most sensible immediate action.

For this sow, continuous provision of appetising feed and plenty of liquids is essential. As long as these do not include kitchen scraps and are prepared away from a human kitchen, porridge oats and apple juice can be combined into an easy-to-eat gruel. The piglets will likely require supplementary feeding using sow milk replacer and/or creep feed.

Whether antibiotics and NSAIDs are appropriate for this sow is debated. Infection by Helicobacter suis may play a role in the development and severity of gastric ulcers. However, Hellemans et al (2007b) found that H. suis was present in 90% of adult pig stomachs at slaughter. There is a risk of bacteraemia when the endothelium is disrupted, meaning antibiotic therapy could be justified on these grounds. An association between the use of NSAIDS and the presence and severity of gastric ulceration has been described in pigs (Ghidini et al, 2023). However, analgesia is likely to improve appetite and, therefore, protectively fill the stomach, creating a conflict of priorities here as well. In this case, communicating the pros and cons to the owner may facilitate collaborative decision-making around treatment.

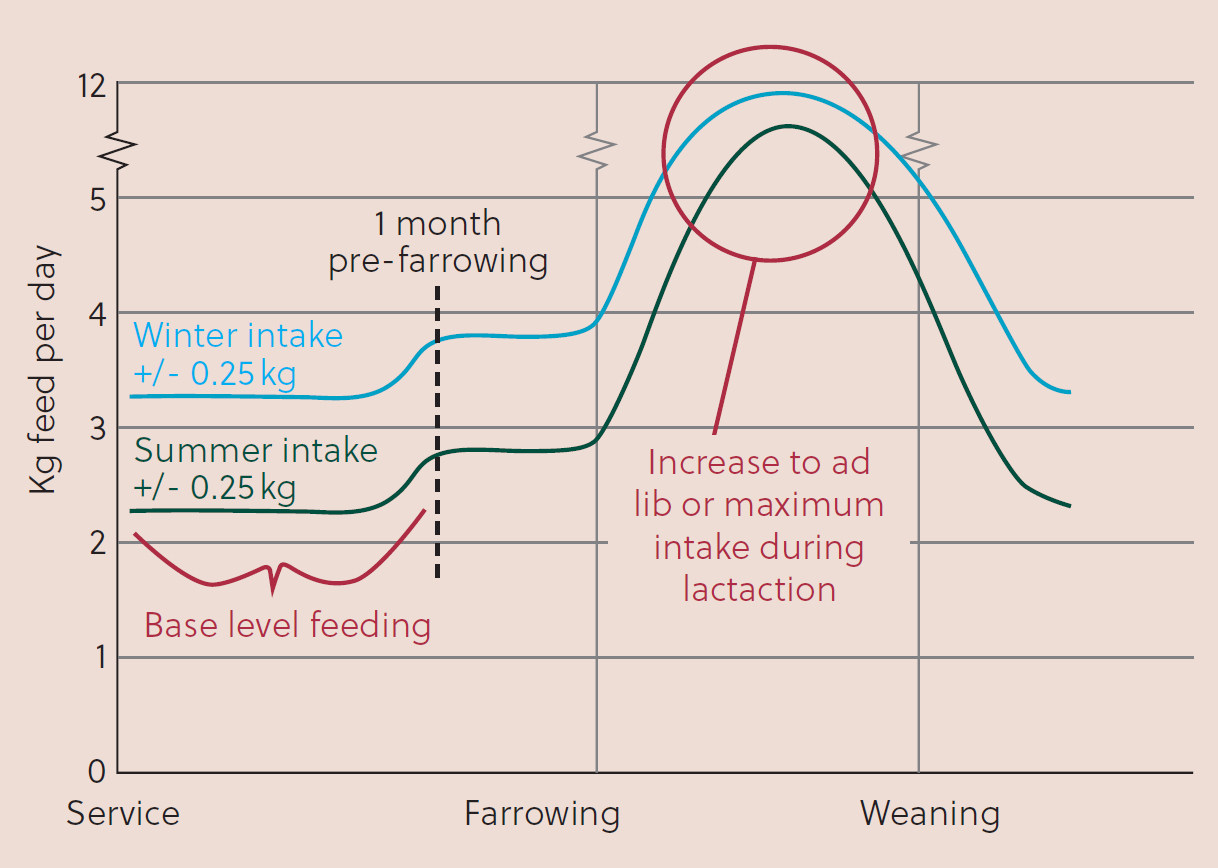

In addition to this, advice for future prevention could include ensuring that the feed type and quantity are suitable for the stage of reproduction or lactation. A sow at peak lactation requires ad lib—up to 12 kg per day—of good quality (Figure 9). The keeper must ensure that feed intake increases as expected towards peak lactation by frequently offering appealing and fresh food in meal sizes that will not overwhelm the sow, along with plenty of water—up to 50 L per day. Small feed particle size is a risk factor for ulcer development. Somewhat counterintuitively, particles are ground to a small size to create pelleted feed. Although pelleted feed is regarded as beneficial to avoid food waste, meal feed may be preferable when ulcers are suspected. It is also important to monitor the body condition of lactating and dry sows and to adjust their feed accordingly.

To enhance the well-being of large litters, it is advisable to proactively provide creep feed and may sometimes be neccessary to provide supplementary milk. Creep feeding helps to reduce unnecessary metabolic demands on the sow while also preparing piglets for a smoother transition away from a milk diet. Alongside this, veterinarians should evaluate other risk factors for the development of gastric ulcers, such as high wheat feed content, and assess whether viable mitigation strategies can be implemented.

Case 3

History

A three-day-old piglet, the runt of the litter, is fading and has yellow, pasty diarrhoea. The sow experienced a prolonged farrowing and appeared to produce less colostrum than with previous litters. Sows are routinely vaccinated for erysipelas, parvovirus and Escherichia coli before farrowing.

Physical examination

The abnormal findings in this sick piglet are sunken eyes sunken eyes, yellow, pasty diarrhoea and a rectal temperature of 37.3°C.

Discussion

This situation is familiar from a ruminant perspective. E. coli septicaemia is common in a 3-day-old calf, lamb, or piglet that is scouring and dehydrated following a difficult birth and poor colostrum intake. Other differentials include rotavirus and Clostridium perfringens. NADIS’ webpage on piglet scour contains further information (NADIS, undated-a). Poor colostrum intake in this piglet and impermeability of the pig placenta to antibodies make the sow’s vaccination status irrelevant.

Treatment and Prevention Plan

As with calves and lambs, rehydration is the most important intervention (Figure 10). This is achieved through regular bottle feeding at first (at least every 2–3 hours initially), with a view to encouraging the piglet to drink from a tray of sow milk replacer, provided the veterinarian can observe the sick piglet drinking and not being outcompeted by its siblings.

Trimethoprim/sulfonamide (TMPS) is a common treatment choice for the individual scouring and septicaemic piglet until culture and sensitivity results can be obtained, given that it is likely to treat disease due to E. coli – although some resistance is reported (VMD, 2024) – and coccidiosis. TMPS is considered suitable as a first line antibiotic by PVS (2020). Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medicines should be avoided; neonatal diarrhoea is listed as a contraindication (NOAH, 2025a; 2025b), and the (<1 kg) piglet’s weight would challenge administration.

Regarding prevention, risk factors for piglet scour (including chilling, poor colostrum intake and poor hygiene) must be interrogated for this holding. More precise preventative measures will depend on the causative organism(s), and submitting diagnostic samples is crucial to establishing this. The risk factors for difficulty farrowing should also be considered. AHDB’s guidance on colostrum management can be consulted for more information (AHDB, 2025b), as well as NADIS’s on the farrowing process (NADIS, undated-b). After a difficult farrowing, consider supportive care and supplementary colostrum/feeding.

Hand-feeding sick or orphaned piglets is time-consuming and onerous; the same could be said for each of these cases, where supportive care is essential. If the owner is unwilling or unable to do this, euthanasia may be the most welfare-friendly option. The Humane Slaughter Association (2025) website and PVS’s casualty pig document contain information on the humane euthanasia of pigs on-farm (PVS, 2013).

Conclusions

The principles of clinical reasoning apply to pigs as they do to other species. With a few key pieces of species-specific knowledge, pig cases can be approached thoroughly and systematically. While empirical treatment may be appropriate in some cases, integrating structured reasoning with management and prevention strategies improves care. Clear communication supports better pig welfare, client relationships and veterinary confidence. LS

For support with challenging cases

Some cases may remain unclear or not progress as expected. The APHA diagnostic service can be contacted for testing advice and/or to submit samples or carcasses for post-mortem examination. This is through contacting your nearest APHA Veterinary Investigation Centre or post-mortem partner; or by emailing APHA’s Pig Expert Group (https://www.gov.uk/guidance/vets-contact-apha-to-get-expert-advice-on-unusual-animal-disease).