References

Clinical findings from 218 downer cow cases in dairy cows from Gippsland, Australia

Abstract

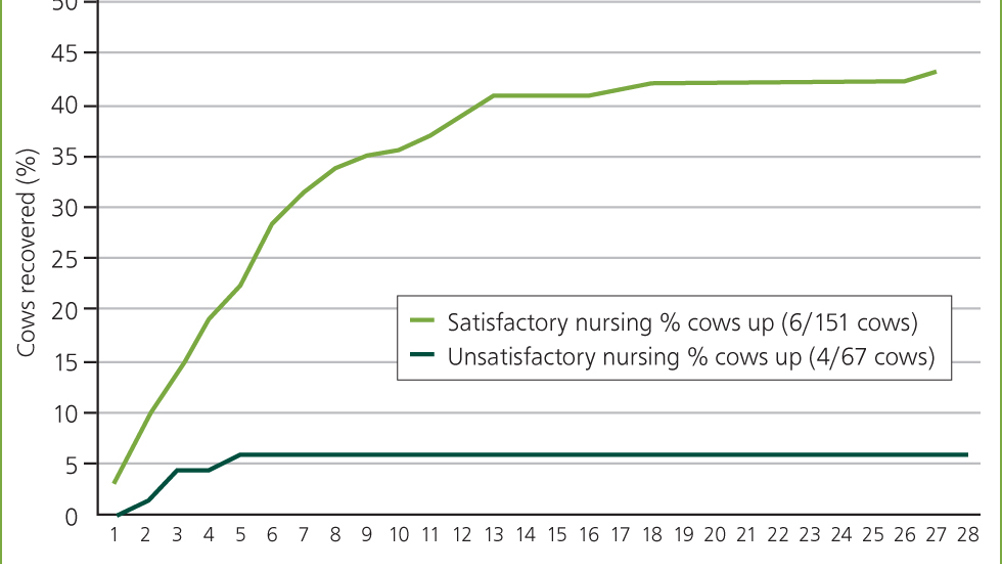

218 downer dairy cow cases under commercial farming operations in South Gippsland, Australia were investigated. The likely cause of the initial recumbency, evidence of secondary damage and the conditions under which they were cared for were recorded to analyse the relationships between primary cause, secondary damage, nursing care and outcome. 69 (32%) cows eventually recovered and of the 149 (68%) cows that did not recover it was judged by the researcher that 108 (72%) cows did not recover solely from the secondary damage that they sustained after becoming recumbent. ‘Clinically important’ secondary damage was recorded in 173 (79%) cows, which increased the risk of non-recovery by approximately three times (RR=3.33; 95% CI 2.36–4.68). 151 (69%) cows had been nursed ‘satisfactorily’ and 67 (31%) cows were nursed ‘unsatisfactorily’. The relative risk of developing clinically important secondary damage for cows nursed ‘unsatisfactorily’ was 1.23 (95% CI 1.09-1.38) and for non-recovery was approximately sevenfold greater (RR=7.21; 95% CI 2.74–18.98) when compared with those cows nursed ‘satisfactorily’. When veterinarians attend downer cows it is important that they carefully look for secondary damage and actively engage in the cow's nursing care rather than just focusing on the primary cause of the recumbency.

Downer cows, defined as bright, alert and responsive cows that have been recumbent for at least 1 day, are challenging for many veterinarians (Eddy, 2004). They can be difficult to examine and the associations between the primary cause of the recumbency, the secondary damage as a result of their recumbency, the conditions under which they have been cared for and their outcome are oft en poorly understood.

The term downer cow syndrome was originally coined to describe persistently recumbent cows, usually following hypocalcaemia (milk fever). Over the years it was associated with many conditions (Kronfeld, 1970), but Cox et al (1982) showed ‘ischaemic necrosis of the caudal thigh muscles, inflammation of the sciatic nerve caudal to the proximal end of the femur’ and ‘evidence of peroneal damage’ in cows where downer cow syndrome was experimentally induced by maintaining sternal recumbency in healthy cows for up to 12 hours using halothane anaesethia. Their model of pressure-induced damage to the hind limbs became the accepted explanation for downer cow syndrome. This concept was further explained by Malmo et al (2010), who described downer cow syndrome as ‘associated with the pathology that develops secondarily to prolonged recumbency’. They listed hind limb muscle and nerve damage, radial nerve damage, coxofemoral dislocation, fracture of the femoral neck, and further skeletal injury, such as haemorrhage in or rupture of the adductor or gastrocnemius muscles as likely secondary damage in downer cows (Malmo et al, 2010).

Register now to continue reading

Thank you for visiting UK-VET Companion Animal and reading some of our peer-reviewed content for veterinary professionals. To continue reading this article, please register today.